Strings Attached

27 November 2015

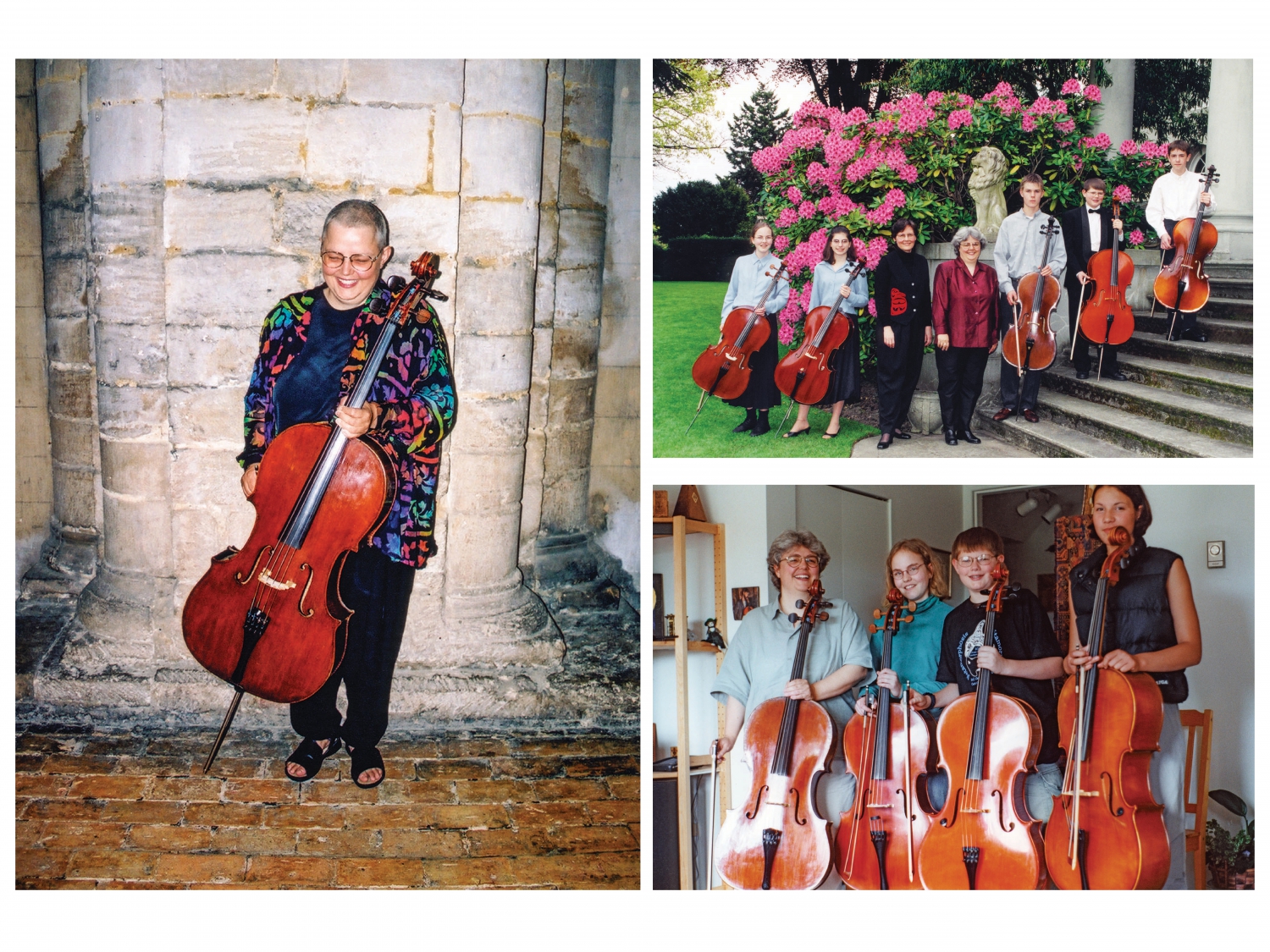

Friends continue a cello teacher’s dream of giving everyone a chance to play

Carolyn Finlay remembers her son Eric’s first cello lesson vividly. His teacher, Catherine Carmack, offered to show the five-year-old a new way to slice an apple. She bisected the fruit sideways through its equator, and held up one white-fleshed half with a five-seeded star clearly visible at its centre. “She said, ‘There’s a star inside all of us. That’s what you do when you play the cello; you’re learning how to find your star,’” recalls Finlay.

There’s a star inside all of us. That’s what you do when you play the cello; you’re learning how to find your star.

Carmack had captivated not only her young son, but his mother as well. An accomplished pianist herself, Finlay had never heard a teacher explain so explicitly how to play from the heart. “It was remarkable. No one had ever taught me music like that before,” says Finlay. “There’s a star in you and you can express it!”

Over the next 10 years, Finlay took over piano accompaniment for all of Carmack’s students’ recitals and exams. She would eventually become Carmack’s performance partner, playing duets with her friend around the Lower Mainland as well as at music festivals in England. As the “pianist in the room,” says Finlay, she witnessed more than anyone Carmack’s heartfelt teaching style. She would ask students what they were thinking about when they played, remembers Finlay, and they would confide the worries or memories that were affecting the resonance of their sound that day. “She believed you had to be able to open up yourself in order to open up the inner meaning of the music.”

In 2003, Carmack suffered a relapse of cancer from an illness seven years earlier. A performance tour she was arranging for eight senior students had to be postponed while she embarked on a course of chemotherapy. Unfortunately, the chemotherapy weakened her immune system over several months, so that when she developed a blood infection later that year, Carmack died within hours. She was 46.

It was a shock to everyone who knew her. Not only had her students lost a beloved teacher, many felt they had lost a confidante and mentor. And because of Carmack’s generosity, some had even lost a benefactor. Carmack had believed so strongly in affording everyone a voice through an instrument that she had given free lessons to students who couldn’t afford to pay and funded scholarships for music camps, junior symphony tuition and performance tours.

But Carmack’s largesse did not stem from personal wealth, for she had never experienced the luxury of silver spoons or free rides. Her father left the family when she was 15, and her mother returned to England and remarried when Carmack was in her late teens. Carmack obtained loans to cover living expenses and tuition while she studied music at UBC. Two decades later, says Finlay, she was still paying these off.

As soon as she graduated, she began teaching music full time in the North Vancouver school system, at the Waldorf School and at the Vancouver Academy of Music, as well as from her home, an airless basement rental suite. Just before young Eric had gone for his first lesson, Carmack had returned from a year abroad at Cambridge University studying music’s effect on the brain. Her thesis was approved for review, but as Carmack could not afford to return to England to defend it before a panel, she never earned her master’s degree. But rather than ask anyone for money, she kept it a secret, recalls Finlay.

At the memorial service, friends discovered that each had been the recipient of some personal kindness on Carmack’s part. Distressed to think that no more aspiring musicians would benefit from Carmack’s selflessness, Finlay decided to set up a scholarship fund in her friend’s name. She approached Vancouver Foundation and found it surprisingly simple to set up the Catherine M. Carmack Memorial Cello Scholarship Fund. To produce enough for a yearly payout without reducing the principal, Finlay learned that the fund needed only $10,000.

Since the fund must grant to a registered charity, Finlay suggested the organization “closest to Catherine’s heart.” The Vancouver Cello Club was a natural choice because it exists to promote and share a mutual love of the cello between students, teachers and master players – ideals that Carmack had held dear since her own student days.

Once the fund was in place, Finlay spread the word to all of Carmack’s students and friends. After several fundraising recitals and many generous private donations, the fund had double the minimum. In 2005, the Club began awarding $1,000 in scholarships to promising students unable to afford intensive music summer camps.

It’s fitting, believes Finlay, that the scholarships will help young people find expression through music. Carmack had a special affinity for children, teens and anyone suffering in a way they could not fully articulate. She taught them how to speak with their cellos, and how to listen.

“She was there to give a musical voice to ordinary people, for their own richness of being. If they thought they could express themselves through a cello, she was there to help.”

| By: Wendy Goldsmith | Photos: Courtesy of Carolyn Finlay |